- Home

- Suzanne Morrison

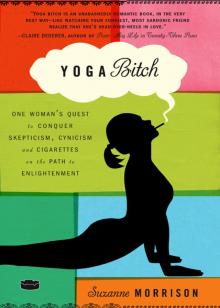

Yoga Bitch

Yoga Bitch Read online

Copyright © 2011 by Suzanne Morrison

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Three Rivers Press and the Tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morrison, Suzanne.

Yoga bitch : one woman’s quest to conquer skepticism, cynicism, and cigarettes on the path to enlightenment / Suzanne Morrison.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Morrison, Suzanne. 2. Spiritual biography. 3. Yoga. I. Title.

BL73.M667A3 2011

204′.36092—dc22

[B]

2010041940

eISBN: 978-0-307-71745-0

Cover design by Jessie Sayward Bright

v3.1

for

KURT ANDERSON

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Indrasana

2. Holy Ghosts

3. The Body Electric

4. Awakening, Reawakening

5. The Prisoner

6. Nobody’s Child

7. To Keep My Love Alive

Epilogue: The Healer

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1. Indrasana

… and before Kitty knew where she was, she found herself not merely under Anna’s influence, but in love with her, as young girls do fall in love with older and married women …

—LEO TOLSTOY, Anna Karenina

Today I found myself strangely moved by a yoga teacher who spoke like a cross between a phone-sex operator and a poetry slam contestant. At the start of class, she asked us to pretend we were floating on a cloud. As she put it, “You’re oh-pening your heart to that cloud, you’re floating, you’re blossoming out and tuning in, you’re evanescing, yeah, that’s right, you’re evanescing.”

I briefly contemplated giving the teacher my yoga finger and walking out. I’ve been practicing yoga for close to a decade now, and at thirty-four I’m too old for that airy-fairy horseshit. As far as I’m concerned, floating on a cloud sounds less like a pleasant spiritual exercise and more like what you think you’re doing when you’re on LSD while falling out of an airplane. But I tuned out her mellifluous, yogier-than-thou voice and soon enough found myself really meditating. Of course, I was meditating on punching this yoga teacher in the face, but still.

At the end of class, she asked us to join her in a chant: gate, gate, paragate, parasamgate … which means, she said, her voice shedding its yogabot tones, gone, gone, gone beyond. She was young, a little cupcake of a yoga teacher in her black and gray yoga outfit. Maybe she was twenty-five. Maybe younger. She said her grandmother had recently passed away, and she wanted to chant for her and for all of our beloveds who had already gone beyond. In that moment, I forgave her everything, wanted to button up her sweater and give her a cup of cocoa. I chanted gone, gone, gone beyond for her beloveds and for mine, and for the twenty-five-year-old I once was.

I turned twenty-five the month after September eleventh, when the stories of those who had gone beyond that day were fresh and ubiquitous. I was working three jobs to save money to move from Seattle to New York, and whether I was at the law firm, at the pub, or taking care of my grandparents’ bills, the news was on, and it was all bad. So many people looking for the remains of the people they loved. So many images of the planes hitting the towers, the smoke, the ash.

I had never really been afraid of death before that year. I thought I had worked all that out by the age of seventeen, when I concluded that so long as one lives authentically, one dies without fear or regret. As a teenager, it seemed so simple: if I lived my life as my authentic self wished to live, then death would become something to be curious about; one more adventure I would experience on my own terms.

Religion was an obstacle to authenticity, I figured, especially if you were only confirming in the Catholic Church so that your mother wouldn’t give you the stink-eye for the rest of your life. So, at seventeen, I told my mother I wouldn’t be confirming. That Kierkegaard said each must come to faith alone, and I hadn’t come to faith—and she couldn’t make me.

This was all well and good for a teenager who secretly believed herself to be immortal, as my countless speeding tickets suggested I did. But by twenty-five the idea of death as an adventure struck me as idiotic. As callous, heartless, and, most of all, clueless. Death wasn’t an adventure; it was a near and ever-present void. It was the reason my throat ached when I watched my grandfather try to get up out of his chair. It was the reason we all watched the news with our hands over our mouths.

I had recently graduated from college, having postponed my studies until I was twenty-one in order to follow my authentic self to Europe after high school. Now I was supposed to leave for New York by the following summer. Before the attack on lower Manhattan, I had been nervous about moving to New York, but now what was supposed to be a difficult but necessary rite of passage felt more like courting my own annihilation.

Everywhere I looked, I saw death. My move to New York was the death of my life in Seattle, of a life shared with my family and friends. Given the precariousness of our national security, it seemed as if moving away could mean never seeing them again. I remember wondering how long it would take me to walk home from New York should there be an apocalypse. I figured it would take a while. This worried me.

Even when I wasn’t filling my head with postapocalyptic paranoid fantasies, death was out to get me. Once we got to New York, my boyfriend, Jonah, and I would move in together, and I knew what that meant. That meant marriage was coming, and after marriage, babies. And only one thing comes after babies. Death.

I came down with cancer all the time. Brain cancer, stomach cancer, bone cancer. Even trimming my fingernails reminded me that time was passing, and death was coming. Those little boomerangs of used-up life showed up in the sink week after week.

I measured out my life in toenail clippings.

“Stop thinking like that!” my sister said.

“I can’t.”

“Just try. You haven’t even tried.”

My sister, Jill, has always been the wisest, the most grounded, of my three siblings. But she couldn’t teach me how to live in the face of death, not then. But Indra could.

Indra was a woman, a yoga teacher, a god. Indra taught me how to stand on my head, how to quit smoking, and then lifted me off this Judeo-Christian continent, to fly over miles and miles of indifferent ocean, before dropping me down on a Hindu island in the middle of a Muslim archipelago at the onset of the War on Terror. Indra was my first yoga teacher and I loved her. I loved her with the kind of ambivalence I’ve only ever had about God, and every man I’ve ever left.

Indra introduced me to the concept of union. That’s what hatha yoga is all about, uniting mind and body, masculine and feminine, and, most of all, the individual self with the indivisible Self—who some call God.

When I was seventeen, I was proud that I had chosen not to confirm into the Catholic Church. I figured everybody I told—all those sane people in the world who did not share my crazypants DNA—would agree with me. I was right; most of them, especially my artist friends, did. But one teacher, my drama teacher, said something I’ve never forgotten. After rehearsal one day, she listened indulgently while I bragged about my lack of faith, a half-smile on her face. Then she said, “It’s okay to fall away from the Church when you’re young. You’ll come back when people start dying.”

People were starting to die. And as if my drama teacher had seen something

in the prop room’s crystal ball, spiritual memoirs started accumulating on the floor beside my bed. I told no one what books I was reading. If I had, I wouldn’t have said that I was reading them in the hopes of finding God. I would have said that they were works of fiction, really, redemption narratives dressed up in the styles and mores of different times and places. I would never have admitted that what kept me reading was the liberating expansion I felt in my lungs as narrator after narrator was transformed from lost into found.

Maybe that’s what led me to Indra. I don’t know. All I know is that one night in the fall of 2001, I walked in off the street to my first real yoga class. I had done yoga in acting classes, and once or twice at the gym where my sister worked, so I knew the postures already. I had never been especially attracted to the idea of a yoga practice, but now I walked into this studio as if I had spent all day weeping in the garden like Saint Augustine, waiting for a disembodied voice to sing, Pick your ass up off the lawn furniture and go work your shit out, for the love of God.

That night, I stepped out of the misty Seattle dusk and into a warm, dimly lit studio. Candlelight glinted off the hardwood floors. The low thrum of monks chanting emanated from an unseen speaker, and a stunningly beautiful woman with straight, honey-colored hair sat perfectly still in front of a low altar at the front of the room. Indra. She wore flax-colored cotton pants and a matching tank top. Tan, blonde, tall: I’ve never been one to worship at the altar of such physical attributes. It was more the way she sat, still and yet fluid, that attracted me, and her eyes, which were warm and brown, with friendly crow’s-feet lengthening toward her hairline.

Soon we were stretching and lunging and sweating. The lights stayed low and her voice stayed soft, so that eventually it almost seemed as if her instructions were coming from inside my head. Toward the end of class, we were doing something ridiculously hard, lying on our backs with our legs hovering a foot off the ground until my abdominal muscles felt like they would burst. Without realizing it, I had folded my hands at my solar plexus. “That’s a good idea,” Indra said, nodding at my hands as she kneeled beside me to adjust my hips. “It always helps me to pray when I don’t know what I’m doing.”

I had to laugh at how baldly she acknowledged my incompetence, but even as I laughed I wanted to point out to her that I hadn’t been praying. I had been thinking, Kill me. Please kill me. I wouldn’t pray. Who on earth was there to pray to? Or, for that matter, who not on earth?

But by the end of class I was thanking the gods for this teacher. Before I left, I wrote her a check for a month’s worth of classes, and told her I’d be back soon.

Indra co-owned the little studio on Capitol Hill with her partner, Lou. Lou was older than Indra by at least ten years, but they were both the same height and weight—both tall, both strong. That was one of the first things Indra told me when I asked her about Lou, as if this were proof that she and Lou had been designed for one another. I didn’t go to Lou’s classes much—afterwards I always felt like my tendons had turned to rubber bands, but he was too intense and his gaze too penetrating for me. Also, his classes were full of smelly drum-circle types. But Indra’s classes felt like home.

I don’t know if I can fully express how bizarre a statement that was. Indra’s classes felt like home. Not long before I met Indra, I would’ve mocked myself mercilessly for saying such a thing. Before her, my idea of exercise was walking up the hill to buy smokes. Rearranging my bookshelves. Having sex. Maybe an especially vigorous acting exercise. Most of the time I lived above the neck.

I’m a reader. Being a reader means I like to be in small, warm places like beds and bathtubs, whether I’m reading or snoozing or staring at dust motes in a shaft of sunlight. At twenty-five, the idea of physical exertion put me in a panic. I would actually get angry, sometimes, when I saw people jogging, sort of in the same way I would get angry at people who wanted me to believe in a God who requires us to be miserable all the time if we’re to get into heaven. All joggers believed in an afterlife, I figured. They must; why else would they be wasting so much time in this life, which by all rational accounts is short and finite? In my hometown the population was split. Half the people in Seattle jogged and believed in an afterlife, and the other half read and believed in Happy Hour.

At twenty-five I was firmly entrenched in the latter half of Seattle’s population, so it came as an absolute shock, not just to me but to everyone who knew me, when I found myself going to Indra’s yoga studio in leggings and tank tops four times a week, sometimes more, to sweat and stretch and experience what it was to use my body for something other than turning over in bed. I would arrive at the studio feeling like I’d spent the day tied by the ankles to Time’s bumper, my fingernails scraping the earth. I walked out upright, fluid, graceful, as if Indra herself was the pose I needed to master. My acting teachers were always telling us to find characters through their walks, that if we could physically embody our characters, we could begin to map their mental and emotional landscapes. So, when I walked somewhere alone, I walked like Indra. Spine erect, chin lowered, I was all straight lines when I was Indra—tall and long, my softer curves elongating into her ballerina sinew. My steps were deliberate and faithful. No need to look down; Indra would trust the terrain.

In class I watched the way she eased her body into each pose. No matter how excruciating the posture was for me, no matter how mangled and unbalanced I felt in it, Indra’s face was always calm. She seemed to be somewhere beyond the pose, even, as if she were only faintly aware that her body was being sculpted into the posture by an unseen hand, her arms pulled into perfect alignment, trunk twisted and massaged, the arches of her feet caressed into graceful caverns. Her toes splayed out one by one like the feathers in a burlesque dancer’s fan.

Indra made me want to buy things. Things like hair straighteners. Even Indra’s hair expressed a certain serenity, while my wavy, fluffy hair, forever escaping its hairbands, said no such thing about me.

She made me want to buy yoga mats and books with titles like City Karma and Urban Dharma and A Brooklyn Kama Sutra. I left her class every morning and walked straight to Trader Joe’s, as if the purchase of organic cheese and tomatoes and biodynamic bubble bath was an extension of my yoga practice.

And according to Yoga Journal, it was.

But the most amazing thing of all was that Indra made me want to quit smoking. After class one morning, just as I was putting on the long wool coat I had worn out to the bar the night before, she asked me if I was a smoker. I told her I was, you know, sometimes—like when I drank, or when a girlfriend was going through a breakup, or like, you know, when I was awake.

“But I’m in the process of quitting,” I said.

Indra laughed, a deep, appreciative belly laugh. “I know how that goes,” she said. She lowered her voice and leaned toward me as if she were about to tell me something she’d never shared with another student. “I was in the process of quitting smoking myself—for about twelve years.”

“You’re kidding,” I whispered back.

She nodded. “But the thing about quitting smoking is, it’s not really a process.” She smiled. “It’s an action.”

It wasn’t the last time Indra would call me on my bullshit. But beyond her words I heard something far more provocative, inspiring and terrifying all at once. I was once you, so one day you can be me.

I wonder, now, if that’s the first time I felt ambivalent about Indra? When for a moment I saw not just my potential to be her, but her potential to be me? I don’t know. All I know is that soon something happened that made me willing to follow her anywhere, if she would only teach me how to live.

It was Thanksgiving. That year my grandmother wasn’t well enough to join us at my aunt and uncle’s for dinner, but my grandfather would never miss a party if he could help it. In fact, my grandfather usually was the party; now that Gram’s health was failing, we all spent more and more time hanging out at the house to keep Grandpa company. It wasn’t unus

ual for my sister and me to arrive at our parents’ and find our brothers mixing Scotch and waters for Grandpa on a Friday night; all four of us often started our weekends doing just that. This was not a chore. Even my friends liked spending time with my grandfather.

My mom always called her father-in-law an old shoe, the kind of person everybody’s comfortable around, who you can’t help but love right away. My sister called him the Swearing Teddy Bear. Six foot four, with a square head, thick white hair, and bright blue eyes, my grandfather was famous for saying the wrong thing at the right time. When he met my friend Francesca for the first time, he looked her up and down, a sly smile on his face, and said, “Well you’re a spicy little number, aren’t you?” She laughed so hard she almost spat her wine across the table.

When I told him that my best friend from the time I was in elementary school had come out, he said, “That’s fine, but what the hell do those lesbians do together, Suzie? What do they do?”

“They do everything a man and woman do together, Grandpa.”

He wagged his finger, already pleased with himself. “Ah, yes—except for one thing.”

Politically correct, he was not.

Grandpa wasn’t in the best shape. We all tried to get him to ride his exercise bike, and sometimes he would oblige us, pedaling halfheartedly for five minutes, before giving up and requesting a tin of sardines as his reward. Mostly he liked to sit in his big red chair, watching court shows and old British imports, or listening to Verdi and Wagner through his headphones, whistling along to the good parts.

After a long night of turkey and mashed potatoes, my father and older brother were helping Grandpa into the car when he started wheezing. This wasn’t unusual. The mechanics of standing up and sitting down had given him difficulty for some time; twisting and bending and lowering himself all at once to get into a car was a lot for a man who hummed to hide the grunts he made when he tried to tie his shoelaces. But tonight the wheezing started even as he walked down my aunt and uncle’s short driveway, flanked by his two namesakes. By the time he reached the car, the sound coming from his chest was like sucking on taut cellophane, and as he tried to lift his foot to get in, he crumpled against my father. I ran around to the other side of the car and helped guide him into place as his breathing thinned into reedy sips of air pulled through lips molded like a flute player’s. His eyes were panicked. I held on to his arm and willed him to breathe, taking deep breaths to show him how it was done, how he could find his way back to my face and to the car and to another night of sleep. “Come on, Grandpa,” I said, stroking his arm. I breathed deeply over and over again, this is how it’s done, just do what I’m doing, but soon my own breath grew shallow and sharp and I could feel that my face was wet. I was sobbing. Or hyperventilating. Or both.

Yoga Bitch

Yoga Bitch