- Home

- Suzanne Morrison

Yoga Bitch Page 8

Yoga Bitch Read online

Page 8

“We?”

“Yeah, you know …”

“What, educated people? Liberal people?”

“Um, no. Modern people, I guess.”

“You were raised Catholic?”

I laughed. “Isn’t it obvious?”

“I was, too,” she said, “and there was a time when I thought religion was all about guilt and power and politics.”

“Absolutely,” I said, “and you were right.”

“But my whole purpose in being on this planet is to love God. Yoga is about learning to love God. We are God, all of us, and when we ask God for mercy, we are asking ourselves to be merciful. Don’t you think we could all stand to be more merciful with one another?”

And what was I supposed to say to that, No?

When I was little I thought I could sense God following me around, observing my performance as a human being, watching me pull my sister’s hair or pretend that Barbie was having sex with Ken. And Skipper. And My Little Pony. These days, if I sense that audience—and I do, more often than I care to admit—I remind myself that it’s just that my narcissism is so powerful it has actually splintered off and begun to live outside of me.

Indra asked if I’d studied my niyamas. The yamas and the niyamas are sort of like the yogic Ten Commandments. You abstain from the yamas—sex, lying, stealing. And you observe the niyamas—you practice contentment, that sort of thing.

Indra said there were three niyamas she wanted me to focus on. “You could think of them as a trinity, since you’re familiar with the term.” I groaned and made the sign of the cross, which made her laugh.

So she told me that the first was tapas, which means to heat or cleanse. It’s what we’re doing in practice, heating up our bodies through the postures in order to purify them. The idea of tapas, she said, is to learn how to suffer gracefully. To sit with pain until we can transcend it. An idea I love, in theory. It sounds incredibly badass, very Linda Hamilton doing chin-ups in Terminator 2. In practice, however, it makes me want to lie down on the floor and become a lima bean.

The second was svadhyaya, or self-study. This I can accomplish by reading my sacred texts, and witnessing my emotions instead of identifying with them. And keeping this journal. She told me to read the Yoga Sutras, the Upanishads, the Koran, and yes, the Bible.

“Christ.”

“Exactly. Christ was an avatar. He came here to teach us about loving God and each other.”

“Maybe, but I don’t think he wrote that prayer!”

“Well, fine, let’s continue. The final niyama I want you to think about is isvarapranidhana.”

She looked at me, and her eyes were warm and expectant. I wanted to make her happy, but all I could say was “Ishwarra whatana?”

“Love of God,” she said. “Surrendering yourself to God.”

I nodded, like, sure, Indra, I’ll do that right now.

The weather shifted, suddenly. A gust of wet wind moved across the floor. Indra pulled her hair into a ponytail without missing a beat.

“You’re afraid of death,” she said. “You said so our first day in Circle. You see death everywhere you look, so you’re afraid to act. If you can love God, surrender to God, you can live in the moment, free of anxiety. Without God? You look ahead and see traps and pitfalls, you look behind and you see loss and death.”

Rain started beating down on the roof of the wantilan. Indra told me to think about Lot’s wife.

“You know the story—God destroys the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and spares Lot and his family, provided they leave the city immediately and without looking back? He is asking them to have faith. Until you have faith in God, you will always be turning back, like Lot’s wife, looking back out of fear of death and change. And we know what happened to her, right?”

“Pillar of salt.”

“Right. Loving God allows you to simply move forward without trying to relive the past or divine the future. At your age you need to be moving forward, don’t you think?”

“Okay,” I said. I swiveled away from Indra to stretch my legs in front of me. “But … ah!” I shook my head. Could I really practice loving God? God? I felt like I could hear Richard Dawkins and all my old professors snickering from thousands of miles away.

Indra lifted herself off the ground and crouched in front of me. “Answer me this,” she said. “Do you like chanting in Sanskrit?”

“Yes! Why can’t we just stick to Sanskrit?”

“Well, you realize we’re essentially saying the same things. We’re asking God for mercy. It seems to me that, since you can chant in Sanskrit but not in Greek, your problem isn’t with God. It’s with language.”

And that was that. She stood up and left the wantilan, and I joined my yogamates in their color wheel of mats for a between-class meditation session. I watched Indra walk down the steps, into the rain, her eyes fixed forward.

All this coming from a woman who drinks pee, I thought.

Later

When I was about four years old, Grandpa and I went for a walk in the woods behind my house. It was Easter morning, and I was wearing my ballet clothes—powder-blue leotard, skirt and tights, pink ballet slippers, and a tomato-red T-shirt over the whole thing. I’m told I wore this outfit most of my fourth year.

I carried an Easter basket full of jelly beans and Cadbury Creme Eggs, which were, and are, my favorite Easter candy. But I couldn’t make sense of how a rabbit could have gone to the grocery store and bought a bunch of Cadbury eggs without someone noticing him. Which would mean that he might have stolen them in order not to be seen, something that I knew from a traumatic paper-doll experience was a sin.

Naturally, such a possibility troubled me, and Grandpa must have picked up on it. Grandpa’s always been intuitive like that. But I didn’t know how to articulate such a complex ethical issue, so when he asked what was wrong, I told him I was wondering if the Easter Bunny was real.

“No,” he replied. “He’s not. Neither is the tooth fairy.”

I nodded.

“But Santa Claus,” he said. “He’s real.”

I had total faith in Grandpa’s knowledge of the universe, so I believed in Santa Claus for years longer than I might have otherwise. I keep thinking about that, about what a relief it was that he gave me Santa Claus. I was at the age, I suppose, when all the older kids knew the truth about our holiday gods, and it was a relief to have the big-kid knowledge that some of our gods are imaginary, more customary than anything else, but that one is real. My grandfather confirmed that I was right to have doubts while still giving me permission to believe.

I thought of it the moment I sat for meditation with my yogamates, after Indra had left the wantilan. And I keep thinking of it because in the strangest way, I feel relieved.

Not convinced. But relieved.

March 9

I love the church of my youth, I love the church of my youth, I love the church of my youth.

I’m practicing loving it. Samtosha!

You know, it occurred to me today that even if I hated our priest and his rhetoric, there were a few things I loved about Catholicism growing up. The bhakti elements. Like the Balinese stuff, the offerings, the incense, the rituals.

I keep thinking about Gabe’s ordination. It was at St. James Cathedral, in Seattle, before it was remodeled, when the altar was in the nave of the church, not in the center as it is now. We rarely went to the cathedral when I was a kid, but when we did I imagined that there were secret chambers just beyond the altar and the tabernacle, rooms where secrets were kept—secret objects and secret books, maybe even secret people like Opus Dei. Those imaginary rooms were where the sacred mysteries of the world were kept, and the Gregorian singers’ bell tones hung in glass webs like a force field between us.

The ordination Mass was long and repetitive, a real knee-breaker. Every priest in the archdiocese was there to welcome Gabe into the brotherhood, and there were several occasions in the Mass for the priests—hundreds of them, thousa

nds of them!—to approach my cousin in the sanctuary and bless him. Toward the end of the Mass, Gabe was made to lie facedown in front of the altar, the priests surrounding him, so many that they spilled down the altar steps and into the aisles. Gabe’s arms stretched in front of him like Superman flying to heaven.

The priests gathered around, all of them in white robes like so many stern and aged altar boys. They encircled him, each with one arm stretched out, their palms facing the prostrated body of my cousin, and they muttered prayers we in the congregation couldn’t hear. And, oh, the smells and bells were wafting and ringing, and I breathed excitement and jealousy. I wondered what would change if there were women on the altar with them. What if I were up there? In spite of myself, I wanted to be in my cousin’s place, who now would have access to all those secret rooms and secret books. I wanted to be indoctrinated into a mystery.

The Catholic faith is predicated on mystery: the mystery of the Trinity, the mystery of the Immaculate Conception. Miracles abound. I’ve always liked that; if I were to practice, I wouldn’t want my religion to be too practical, lest I start to believe we really know what we’re talking about. Because honestly? I just can’t believe that anyone really knows who God is, if God really does exist.

Gabe quoted Saint Augustine to me once: Si comprehendis, non est Deus. If you understand it, it’s not God. That day I imagined myself in my cousin’s place, being knighted in order to guard over those secrets of life that can’t possibly be understood, but only expressed through ritualized mysteries. I didn’t want to take on any of the duties of a modern priest—from soup kitchens to church renovations to preaching a knowledge of the afterlife and the character of God. No—I wanted to be a knight.

But of course, I can’t expect the Church to conform to my idea of what its rituals should express, can I? And even if I could, they don’t want me. Mystery and reverence belong to the men. And I never saw anything sexy about cutting all my hair off and becoming a nun.

March 10

This morning Indra and Lou told us that they were canceling our afternoon class due to an issue at home. Neither one slept much last night, because just as they drifted into sleep, a ghostly whirring sound came from the kitchen. They got up to see what it was, and discovered that their blender, without any human assistance whatsoever, had somehow managed to plug itself in and start blending.

Why does a blender plug itself in and blend in the middle of the night?

Simple. Because it is possessed.

Indra and Lou have a poltergeist in their blender!

Apparently this is quite a common occurrence on Bali. According to my teachers, legions of spirits wander the island every night, just looking for their chance to break into your house, animate your kitchen appliances, and fuck your shit up.

Indra said that she tried to talk the spirit out of the blender, but it didn’t work. She shrugged and gave Lou a wry smile. “It’s a pesky spirit, this one, but we have to be kind and remember that half the reason a spirit possesses a blender is just to get a little attention.”

Lou was massaging his quadriceps. “Listen, people,” he said. He paused, breathing in sharply through his nose, collecting his thoughts. “Sometimes when you give the spirit the notice it craves, it will move on and leave you alone.”

Indra nudged his shoulder with hers. “We’re pretty used to this sort of thing,” she said. “Spirits just seem to follow us around.”

Jason looked at Indra with wide eyes, like a little boy. “What do you say to a blender to give it the attention it craves?”

Indra laughed, looking down at her legs as she adjusted them in lotus. “It might sound a little funny, but I said, ‘Spirit, I recognize you, you can leave the blender now. Release the blender, spirit, we acknowledge you.’ That sort of thing.”

Baerbel was sitting on her heels next to me. She’s a sixty-five-year-old grandmother from Berlin, and the only person in the wantilan besides me who thinks everything about yoga is funny. She tittered. “Well,” she said, “if you believe in spirits you will see them. If you don’t, you won’t!”

And I thought, Maybe that’s how I feel about God.

Anyway, Indra and Lou have invited some of us over to their house for a ritual purification of the blender. Which would be hilarious to me if I weren’t ecstatic at the prospect of seeing Indra in her natural habitat. I’m a little embarrassed about how happy I am to be one of the chosen four. Jonah wouldn’t recognize me. I can’t stop grinning. Maybe I’m just another pesky spirit who needs to find an appliance to possess in order to get some attention. The first thing I’m going to say when I meet this blender? I understand you.

Sundown

Made is picking us up to drive us to Indra and Lou’s in just a few minutes. Jessica, Lara, Jason, and I have spent the last four hours getting ready. Jessica lit a dozen aromatherapy candles she brought from her massage studio at home, and as the sun went down we turned off the lamps and let the candlelight bounce off the shiny tile floor. Indra and Lou told us to wear sarongs. Su brought over a half-dozen for us to choose from, but we girls couldn’t resist dressing Jason first. He’s prancing around the house in his gold sarong, looking splendid and cheeky in a skirt. He’s wearing a sash of the same gold, a blousy white shirt, and a thick, gold, bandanna-like headband wrapped around his forehead. He’s performing a t’ai chi dance in the candlelight, his shadow looming large against the back wall like a human shadow puppet.

When both girls were out of the bathroom, I stared at myself in the mirror with a candle at my back, so that my brown hair, which is frizzing like all get-out, appeared almost as red as my rust-colored sarong. I looked like I was on fire. In the candlelight my eyes looked deep and round and dark and I could see the shadows of my eyelashes against my upper lids and forehead. I looked like a woman going to an exorcism.

Sigh. My first exorcism. So far, it’s everything I ever dreamed it would be.

The house reeks of sandalwood, amber, and lavender. Lara has joined Jason in his t’ai chi and now they’re doing a sort of mock kung fu. Jessica is laughing hysterically and rolling her eyes around in her head like the satsang dancers we saw the other night. But now the women’s gamelan music has begun, and my yogamates are filing through the shadows and out the door with great solemnity.

See you on the other side.

Later

If I could have designed a house in the trees when I was ten years old, it would have suffered from a poverty of imagination in comparison to Indra and Lou’s home. They live in a secluded corner of the village, in a house they built at the bottom of a long road ending in a cul-de-sac of bungalows just along the edge of the forest. We could still hear the gamelan when we got out of the car, but now it was punctuated with the screams of monkeys coming from just beyond the house.

Their bungalow is nothing like ours. If our place is a mini-mansion, theirs is a cross between a seraglio and a tree house. Only the kitchen and the bedrooms have ceilings. Instead, tall trees grow right through the center of the house, and their glossy, yellow-green leaves provide a natural canopy. You can see patches of darkening sky through the branches.

Gauzy purple and burgundy curtains hang in the doorways along the central corridor. Candles in rice-paper lanterns lighted our way down this main thoroughfare of the house, which is in the open air as well. Made led us through the house and out to the living room, which is more like a large deck that juts into the forest like a dock into a dark green sea.

The purification ritual was conducted by Noadhi, a small, seventy-year-old man Lou referred to as a balian. Balians are healers and scholars of Balinese Hinduism, and they are the most important people on this island with all its pesky spirits. You might say Noadhi is a cross between a priest and an exterminator.

Noadhi was working at a makeshift altar in the middle of the balcony. He was laying out fruits and flowers, cigarettes and cakes, all chosen to entice the spirit out of the blender. Four unlit red candles waited on the edge of the altar, a

nd a long glass bottle filled with an oily-looking orange liquid stood just to the right of the blender. My mouth went dry when I considered what might be in that bottle, and what was to be done with it, if anything. I hoped it was some sort of oily orange holy water—add ice and blend, and you’ve got a specter-free kitchen appliance. Just don’t make me drink it.

Lou was hanging out near the altar, dressed in white with a matching piece of fabric wrapped around his forehead. Jason, Lara, and Jessica made a beeline to join him. I hung back until a voice drifted over from a shadowy corner of the balcony. It was Indra, calling me to join her.

Sitting with Indra in a tree house in the middle of a vast green darkness, drinking spicy tea from a jade tea service among crimson and deep blue pillows: that is what I came here for.

Indra’s different outside of the wantilan. More relaxed. More glamorous, maybe. She reminded me of an actress entertaining at home. Her dark blonde hair was free and ran straight down her back like a sheet of water. She wore a silver and purple silk sarong and a white flower tucked behind her ear. When Lara and Jessica burst into laughter at something Jason said, Indra sat up and spoke in a stage whisper. “Yogis,” she said, “hush. We use our spa voices here.”

I felt a little embarrassed by her choice of words, but my yogamates were duly humbled and took seats facing the altar. Indra turned to me and asked how things were going.

I don’t know how Indra does this, but it’s her greatest power. All she has to do is ask me one simple question and it’s like my head splits open and the contents of my brain spill into her lap. All Indra asked was, “How are you, Suzanne?” and I found myself telling her about Jonah and our plans to live together in New York, I told her about my grandparents and my sister and how sad and guilty I feel moving away from them. I told her that I wanted to change and I feared changing. I told her what I have done and what I have failed to do.

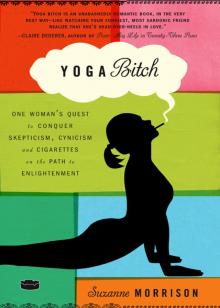

Yoga Bitch

Yoga Bitch