- Home

- Suzanne Morrison

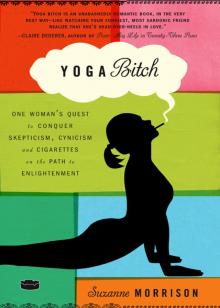

Yoga Bitch Page 9

Yoga Bitch Read online

Page 9

And then something slipped out that I didn’t even know I was thinking. I said, “I don’t even know if I want to live with Jonah in New York.”

The balcony was so quiet; I heard no voice but my own. I glanced at the altar to make sure no one was listening; thankfully my yogamates were meditating with Lou.

After a moment Indra said, “We’ve got a lot in common, Suzanne.”

“Yeah?”

She nodded and went silent. Lou and my yogamates began chanting. The sound wrapped around to our end of the balcony. I felt like a character in the Mahabharata, receiving counsel from some otherworldly sage. Or from a god who had once been mortal.

Indra sipped her tea with both hands wrapped around her green cup. “That’s one of the problems with doing anything for a long time. Staying home, for instance. The longer you stay, the more you believe your identity is wrapped up in the people and things around you. You become trapped. It seems as if you fear change because you can’t let go of this illusion of yourself as being what? The good granddaughter? The girlfriend who can’t choose between her boyfriend and her family? Seems as if your fear of change is really just the same fear of death you mentioned in our first class.”

“So how do you fix all of that? How do you leave your family? When you love them, I mean.”

“Practice dying.”

I laughed, but she was serious. She said to embrace each change as if it were a small death. That I should just dive in and let my world fall apart and rebuild itself. That if I can embrace change, I can embrace death, and that is the secret to liberation.

“But, Indra,” I said. “That sounds hard.”

Indra smiled and glanced at the altar, at my yogamates chanting with Lou. She was silent for a long time; I was beginning to think she wasn’t going to talk anymore when she started to speak very softly, very gently, as if the words were sharp and she had to ease them out in order to not be cut.

She told me she was married once. “A long time ago. And I loved my husband. But I could never shake the feeling that I needed to leave. When I imagined a future with him, all I felt was dread. I think I knew that if I stayed, I wouldn’t be brave enough to change in the ways I needed to change. You know how people who love you hate it when you change?”

I nodded.

“So, one day—it was actually after my first meditation class—I did it. I left. Got in the car, drove cross-country. Left the house. Left the husband. Left the dog. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But then! Then I could grow. I could find God. Until I met Lou, I lived like a monk. Just me and yoga.”

I didn’t know what to say. Well, if I am completely honest with myself, I think I felt both inspired and judgmental. Inspired because I think there’s a secret part of me that would like to drop my entire life off a cliff and watch it break into a million pieces. But judgmental, too: I knew what my family would say. Gram would say, Marriage isn’t a bed of roses, it takes work. My mother would say she was selfish, that she had broken a vow. Isn’t that what Indra just said? That her own needs were more important than her marriage? Her desire to find herself was more important than her promises? But before I could find the words to articulate all of that, Indra stood up. I looked over at the altar to see Noadhi lighting the first of the red candles. The ceremony was about to begin.

The moon was three-quarters full, illuminating the altar and making Noadhi’s white costume glow. Noadhi asked us to stand in a semicircle facing the altar, and then he walked among us with a bowl of holy water in one hand and a lotus flower in the other, the bloom captured between his third and fourth fingers, facing his palm. He dipped the lotus flower in the holy water and then sprayed each of us in turn, just as priests do in Mass. Next he splashed water into our cupped palms and told us to drink. And we did. We slurped it up like it was spring water at the end of a long hike.

The water was just trickling down my throat when I thought, Holy shit. Is this water purified?

I really, really hope that Noadhi used an actual filter to purify the holy water, and not just prayers. But after a half-dozen palmfuls of water, I relaxed a little, and then I found myself hoping that the water wasn’t just pure, but purifying; that it would clean me out, make me new.

Noadhi pressed white rice kernels to our foreheads and temples. Then he turned toward the altar and lifted his arms above his head and closed his eyes. He stood like this for a long time. I was about to nudge Jason to see what we should be doing when I realized that everybody around me had their arms up and their eyes closed, and they all appeared to be praying fervently for the blender. Which begged the question, What sort of prayer does a person make for a possessed kitchen appliance?

I lifted my arms and closed my eyes, blinking away a few errant rice kernels. Out, spirit! I commanded. In my head. And then I almost lost it. It took some serious deep breathing to keep myself from cracking up.

Purity, Tranquillity, Calmness, Bliss. I pray to Jessica’s aromatherapy candles, including the one called “Tibetan Rejuvenation,” please calm and purify and rejuvenate this poor blender, which is so dear to my teachers.

I opened my eyes. Twelve arms were still up in the air.

Hail Mary, I prayed, fix the blender. Let it blend only when expressly asked to do so.

Pretty soon I let my mind wander away from the blender and back to my conversation with Indra. I imagined a younger version of her driving cross-country, alone. Throwing herself into her car. Her long hair whipping in the wind. Surrendering herself to whatever life brought her. Her heart so open she could even find God.

Hail Mary, full of grace, the blender is with thee. Blessed is it amongst kitchen appliances, and blessed is the fruit that it shouldst be blending.

Oh, help. My arms were so heavy. There were rice kernels in the corners of my eyes, tickling my eyelids. I was starting to panic. Heal, blender, heal! Go toward the light, Carolann!

I opened my eyes and decided that I didn’t like rituals that made me feel like my arms were going to break off at the shoulder. Come on, y’all, I wanted to say, we’re praying for a blender.

And then I smelled something marvelous. Something familiar and comforting. Noadhi was sitting on his haunches next to the altar, smoking a cigarette and watching us. He smiled at me. “So, that’s the end,” he said.

We sat as Noadhi passed out the blessed fruit and flowers from the altar, his cigarette dangling from his mouth. He told us it’s good luck to eat the offerings from a purification ritual. We formed a small circle in front of the altar, Indra and Lou looking casual and relaxed, as if we were just a group of friends gathered for a party. We were chatting quietly and eating apples and rice when Lou cleared his throat.

First he wanted to offer Jason the bottle of oily orange liquid that was still sitting on the altar, next to the blender. It was some sort of Balinese concoction for ridding the body of parasites. I was so relieved by this news, I actually wrapped my arm around Jason and side-hugged him. “Can’t wait to watch you drink that,” I said.

He put on a thick Cockney accent. “I’ll pour it down me froat like a pint,” he said, tipping the bottle back and pretending to chug it.

Lou laughed at that, which I found shocking. “It might not taste as good as a pint,” he said, “but it should make you feel better.” He rubbed his knees. “We also have a small announcement,” he said, looking around at each of us before settling his gaze on Indra. “Indra and I have decided to get married. We’ll be celebrating with a Balinese wedding at the end of our retreat.” He rubbed his neck, and for a moment a sweet, modest smile softened his features. “Noadhi will be performing the ceremony.”

My yogamates and I burst into applause, and Noadhi watched us, laughing and shaking his head. We clapped and whistled, Noadhi laughed, and Indra leaned into Lou, fitting herself right under his arm. Her sarong spread into his lap where her leg rested on his. Lou looked down at her, and his eyes on her were kind and soft, completely unlike the Lou I was afraid of in class. For an instant, my eyes beca

me wet and I didn’t know why. Something was piercing me just below my sternum.

I’ve been thinking about it all night, and I know what it is, now. They were transformed by their affection for each other. Singly, they were two teachers. But at their home, telling us of their future together, they were something else. They were a world unto themselves. That is something I have never experienced before. Something I want. Maybe Jonah and I can create that kind of love when we start living together. But what if we can’t? God, when I think about what Indra had to do to get where she is now—the years of solitude, leaving a man she loved to follow a path with no guarantee that it would lead her to wisdom and a new, deeper love? Terrifying. And, well—inspiring.

Before we left, I excused myself to use the bathroom, and crept past the bedroom and the kitchen, dying to look more closely but not wanting to be a snoop. The bathroom is as much of a curiosity as the rest of the house. The floor around the toilet and shower is a loose bed of smooth river stones. There’s no ceiling over the toilet, so I peed while looking at the stars. Then, washing my hands, I couldn’t resist the urge to look around. I lingered over Indra’s toiletry bags, and without touching anything I could make out mascara, eyeliner, lip gloss, and lipsticks. She has as many organic and “all natural” beauty products as Jessica. Tucked in the corner of the countertop, between an olive-green bag that was as rough as burlap and the oval-shaped mirror, was a tiny yellow travel candle. I picked it up and smelled it; it smelled like Indra, clean like lemon, and warm with something like clove. I turned it over to see its name. “Renaissance Woman,” it read.

3. The Body Electric

O I say these are not the parts and poems of the body only, but of the soul

O I say now these are the soul!

—WALT WHITMAN,

“I Sing the Body Electric”

Have you ever stood near a drum circle and secretly wanted to join in? To just throw aside propriety and irony and get all sweaty and Noble Savage-y?

Yeah. Me neither. Drum circles look strenuous. And smelly. But drum circles are probably the only ritual I haven’t wanted to try. I love rituals, even toasts at weddings. I love them for the way they bookmark time, for the way they enable us to say, out loud, that this moment means something. That we must remember this. These words and choreographed gestures pull us back from oblivion to insist that this life matters, all of it.

I suppose I’ve spent much of my life trying to find the perfect ritual. When I was a kid, I relished the elaborate rituals my elementary school best friend and I made up to worship Mary, virgin queen of the baby dolls. In middle school, as I began to think that I couldn’t be both a feminist and a Catholic, I joined a Presbyterian choir, hoping maybe the Protestants—my father’s people—would have something for me. That didn’t last long, simply because there weren’t enough rituals to keep me excited. Everything with the Presbyterians was so practical, so pragmatic, as if Jesus himself were just a dude and a buddy and not a man-God who could walk on water. The closest thing to a ritual I could get consisted of sitting around with a cool youth leader, talking about what a cool guy Jesus was until I turned into a cool bowl of mush, inspiring my mother to say, “For the love of God, Suzie, will you stop saying ‘Jesus was totally cool’? You sound like a Valley Girl!” After the Presbyterian girls got all the good parts in the Christmas concert, I gave up on my Protestant experiment.

I grew up in a Jewish community, and in seventh grade I spent more time in temple than I’ve spent in church in all the years since. Sometimes, in the privacy of my mother’s bathroom, I would pretend it was my bat mitzvah, reciting parts of my friends’ Torah portions. I loved the thought of being Jewish. My Jewish friends had it all: beautiful rituals in an exotic language, ancient history, family in New York, and some of them, the ones from the reform temple, could look forward to having sex before marriage without fear of going to hell.

In high school I cast longing looks at the chalices and blades my Wiccan friends kept on their altars, and went to the Fremont Solstice Parade hoping that something beautiful would happen. All I got were naked bicyclists. Which was exciting for a girl from the suburbs, but not exactly spiritual.

But whenever anybody brought up God, or the existence of God, I would shake my head. That was the right answer, as far as I could tell. Didn’t mean I couldn’t play at worship. I have a friend who calls himself a Jewish-Buddhist, or a JewBu—he attends a synagogue where they meditate and chant Shalommmmmmmm—and when I asked how he reconciles the God of the Old Testament with the absence of a supreme god in Buddhism, he said, “Maybe I don’t believe in God. Maybe I only believe in culture.”

Maybe he’s on to something.

After the night we exorcised my teachers’ blender, I wanted my entire life to be a ritual. I felt like a novitiate; the Mother Superior, Indra, had given me my orders: be brave, be strong, read your sacred texts, and practice death. That was what I was going to do. I set about reading my books. I meditated between classes, each day training my mind on a different sutra, the way we used to contemplate mysteries while reciting the rosary when I was a kid.

Sometimes my meditation centered on the image of Indra and Lou. On the magnetism between them, that perfect balance of truth and love I saw in them. One day, quite by surprise, I found this in Swami Satchidananda’s translation of the Yoga Sutras:

“The entire world is your projection. Your values may change within a fraction of a second. Today you may not even want to see the one who was your sweet honey yesterday.”

The moment I read these words I wished I could forget them. They acted on me like an incantation, calling up something I had been trying, for months, to put down.

• • •

Jonah liked tarot cards. It was one of the things I loved about him. When I first discovered Jonah’s interest in tarot, I found it very appealing—I imagined us raising our children with weekly tarot readings instead of church, and maybe we would attend the occasional Ren Faire. It made me want to wear moonstones and watch people joust.

I was only slightly disappointed when Jonah told me that his interest in tarot had less to do with magick and more to do with Jungian psychology. He liked working with archetypes. He would choose a number of cards, lay them out on the floor in front of him, and then sit and tell himself a story connecting the archetypes that would illuminate the darker corners of his subconscious.

We were in his apartment late one night, drinking cheap red wine, when I decided it was time. We had been together for over two years, and I was finally ready to ask Jonah to read my tarot cards.

We set up a spot on the floor and lowered the lights. I put on the soundtrack from The Last Temptation of Christ, which was perfectly moody, I thought, just right for the occasion. But Jonah asked me to turn it off, saying it was too cliché. I suggested Dead Can Dance, then, or perhaps Enigma; something with Gregorian chants or stylized wailing in it. No dice.

“Let’s not embarrass ourselves,” he said. “That music makes me feel like I’m at a Ren Faire.”

“Right,” I said, “Ren Faire, yeah. That would be lame.” I was disappointed. If you’re going to perform a ritual, why not go whole hog? It’s all playacting anyway. But my desire to be transported was overwhelmed by my desire to be cool. So I settled in for my reading, happy that Jonah at least allowed the candles to stay lit. The light flickered on the shiny cards as he turned them over: Death. The Magician. The Tower. The Lovers. I looked at the cards for a minute, maybe longer. And then I felt so strange; flushed and cold at the same time. I didn’t want to know what the cards were telling me.

Jonah must have noticed, because he said, “Do you see something? Do you see a story?”

I said no. “No, no,” I said. “I was just spacing out.”

But that was a lie. I couldn’t tell him what I saw—I didn’t even want to tell myself what I saw. Because what I saw was: You. Are going. To leave. This man.

But I love him, I pleaded. He’s my best friend.

>

But the cards didn’t change.

Six months later, I didn’t leave him. I went to Bali.

That night, when Indra told me why her marriage ended, I knew exactly what she was talking about. I didn’t want to acknowledge it, because I thought that my urge to leave Jonah was pure selfishness. How could I throw away a perfectly good relationship just because I wanted to find myself? Why sacrifice Jonah to the whim of some tremulous inner voice that told me to change, but that couldn’t possibly tell me how or why or even what I was supposed to become?

If Jonah and I were terrible at working through problems, it was only because we were too busy having fun together. Discussing our future wasn’t nearly as fun as watching horror movies and seeing how many Bundt cakes we could eat in a week. No one wanted to be the killjoy. So, one minute I thought that it was better to be with Jonah, to enjoy the good things about our relationship and squelch that pesky inner voice that told me I needed to change. The next minute I could see myself on the Aurora Bridge, the suicide hotspot in Seattle, my life with Jonah like a bundle in my hands to be dropped into the cold, dark water below.

But sometimes I thought that maybe all I needed was a change of location. Maybe moving to New York and living with Jonah was the change I needed. Maybe I could prove the cards wrong. I mean, really, when your subconscious pops up with unpleasant surprises, it’s best to ignore it or it’ll have you doing all sorts of crazy things. Better, perhaps, to treat it like an alarm clock and hit snooze until it stops on its own.

March 12

Beneath every banyan tree in the village there’s such an abundance of offerings that every other tree seethes with envy. Papaya trees get nothing, and yet they provide me with my breakfast every morning. The manly, coconut-laden palm trees, same. Maybe they’ll get one or two every few days, but nothing like the banyan. The banyan has as many offerings as some temples.

Today, Jessica and I spent an hour beneath an enormous banyan on the walk between home and the wantilan. We talked about love. We spend a lot of time talking about love.

Yoga Bitch

Yoga Bitch